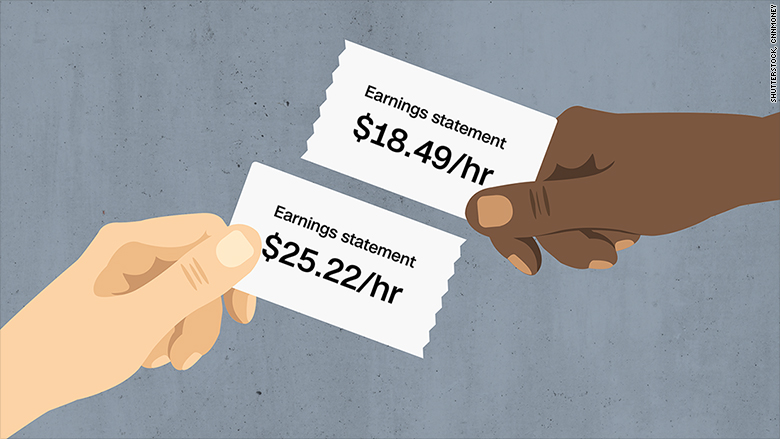

What this report finds: Black-white wage gaps are larger today than they were in 1979, but the increase has not occurred along a straight line. During the early 1980s, rising unemployment, declining unionization, and policies such as the failure to raise the minimum wage and lax enforcement of anti-discrimination laws contributed to the growing black-white wage gap. During the late 1990s, the gap shrank due in part to tighter labor markets, which made discrimination more costly, and increases in the minimum wage. Since 2000 the gap has grown again. As of 2015, relative to the average hourly wages of white men with the same education, experience, metro status, and region of residence, black men make 22.0 percent less, and black women make 34.2 percent less. Black women earn 11.7 percent less than their white female counterparts. The widening gap has not affected everyone equally. Young black women (those with 0 to 10 years of experience) have been hardest hit since 2000.

Why it matters: Though the African American experience is not monolithic, our research reveals that changes in black education levels or other observable factors are not the primary reason the gaps are growing. For example, just completing a bachelor’s degree or more will not reduce the black-white wage gap. Indeed the gaps have expanded most for college graduates. Black male college graduates (both those with just a college degree and those who have gone beyond college) newly entering the workforce started the 1980s with less than a 10 percent disadvantage relative to white college graduates but by 2014 similarly educated new entrants were at a roughly 18 percent deficit.

What it means for policy: Wage gaps are growing primarily because of discrimination (or racial differences in skills or worker characteristics that are unobserved or unmeasured in the data) and growing earnings inequality in general. Thus closing and eliminating the gaps will require intentional and direct action:

- Consistently enforce antidiscrimination laws in the hiring, promotion, and pay of women and minority workers.

- Convene a high-level summit to address why black college graduates start their careers with a sizeable earnings disadvantage.

- Under the leadership of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, identify the “unobservable measures” that impact the black-white wage gap and devise ways to include them in national surveys.

- Urge the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to work with experts to develop metropolitan area measures of discrimination that could be linked to individual records in the federal surveys so that researchers could directly assess the role that local area discrimination plays in the wage setting of African Americans and whites.

- Address the broader problem of stagnant wages by raising the federal minimum wage, creating new work scheduling standards, and rigorously enforcing wage laws aimed at preventing wage theft.

- Strengthen the ability of workers to bargain with their employers by combatting state laws that restrict public employees’ collective bargaining rights or the ability to collect “fair share” dues through payroll deductions, pushing back against the proliferation of forced arbitration clauses that require workers to give up their right to sue in public court, and securing greater protections for freelancers and workers in “gig” employment relationships.

- Require the Federal Reserve to pursue monetary policy that targets full employment, with wage growth that matches productivity gains.

SOURCE: Economic Policy Institute, September 20, 2016